By Paul Hoffmeister, Chief Economist

March 2019

· Assessing market conditions today, we believe that the easy part of this year’s rally in the S&P 500 is behind us and that if there is another 10% or more upside in the market this year, it will be harder to come by. As we see it, if stock market prices were asymmetrically in investors’ favor in late December, they are more symmetric today.

· The outlooks in many of the major macro variables appear to be more balanced, and not too extreme one way or the other. To an optimist, this “setup” suggests that if these variables continue to improve and resolve themselves, then equity markets could experience a sizeable rally from current levels. Conversely, to a pessimist, if these variables deteriorate, then upside should be limited, and there could be another bout of market panic.

· In this month’s client letter, we parse through what we believe to be the most important macro variables today: the Fed, US-China trade, Brexit, the slowdowns in Europe and Asia, and the possibility of a Trump impeachment. And then we explain how, after putting these pieces together, we expect a little volatility in coming months but are generally optimistic about the rest of the year.

· The current macroeconomic outlook could be reasonably described as ambiguous, which seems to be consistent with the relatively flat Treasury curve this year. The general flatness of the curve suggests to us that the Treasury market is sensing some risks farther out on the horizon that could ultimately erupt and harm economic growth; but just not in the near-term.

· There are percolating risks. But importantly, in our view, the dollar (the world’s reserve currency) is fairly stable, deregulation and corporate tax cuts in the United States are still supporting economic growth, and credit conditions are recently improving. Of course, we don’t expect all of the major macro variables in play today to evolve perfectly in the coming months, and some near-term volatility is likely. The UK will need to sort through Brexit, Europe and Asia are relatively weak, and political uncertainties persist in the United States.

In our view, the equity market rebound continued in February mainly because the outlooks for Fed policy and US-China trade continued their positive trajectory. Not to mention, there didn’t seem to be any new, significant macro variables that erupted.

In our January client letter, we believed there was a big opportunity in equities with our forecast for a 15% return in the S&P 500 this year. The projection was based on both quantitative and qualitative factors.

Quantitatively, it appeared that history was on our side: looking at calendar quarters since 1970 in which the S&P 500 sold off 10% or more, the average return during the subsequent four quarters was approximately 14.6%. And qualitatively, we believed that the Fed was going to back off its hawkish plans in 2019 to raise the funds rate another two quarter points – similar to the Fed U-turn in early 2016; and we were optimistic about at least a partial US-Sino trade deal.

With the S&P 500 up 11.1% through February (not including dividends)[1], that 15% forecast looks too low, for now. Assessing market conditions today, we believe that the easy part of the rally is behind us and that if there is another 10% or more upside in the market this year, it will be harder to come by. As we see it, if stock market prices were asymmetrically in investors’ favor in late December, they are more symmetric today.

Another way to look at the current market environment is that the outlooks in many of the major macro variables appear to be more balanced, and not too extreme one way or the other. To an optimist, this “setup” suggests that if these variables continue to improve and resolve themselves, then equity markets could experience a sizeable rally from current levels. Conversely, to a pessimist, if these variables deteriorate, then upside should be limited, and there could be another bout of market panic.

In the following, we parse through what we believe to be the most important macro variables today: the Fed, US-China trade, Brexit, the slowdowns in Europe and Asia, and the possibility of a Trump impeachment. And then we explain how, after putting these pieces together, we expect a little volatility in coming months but are generally optimistic about the rest of the year.

Fed Outlook: “Patient” seems to be the predominant descriptor of Fed policy today. In his testimony before Congress on February 27-28, Chairman Powell said the Fed was “in no rush to make a judgment” about the path of short-term rates. He added, “With our policy rate in the range of neutral, with muted inflation pressures and with some of the downside risks we’ve talked about, this is a good time to be patient and watch and wait and see how the situation evolves.”[2] This policy positioning is in stark contrast to the seeming assuredness that Powell telegraphed in December about raising rates twice this year. In addition to backing off the rate lever, the Fed is also close to announcing updated plans for its balance sheet runoff. Powell indicated in his testimony that the runoff could conclude by year-end.[3]

Powell’s recent testimony reaffirmed for us the dovish comments by St. Louis Fed President James Bullard on February 1st when he said that the Fed’s current policy position (i.e. its “patient” posture) “sets us up for a very good couple of years”.[4]

At the moment, we view Fed policy to be a neutral macro variable – no longer the major negative as it appeared in 2018, while at the same time not a major positive given the relatively flat Treasury curve today.

US-China Trade: In recent weeks, there didn’t seem to be a day that went by without headlines about an imminent deal between President Trump and China’s President Xi Jinping.

According to the Wall Street Journal, both sides are in the final stages of completing a trade deal, which will include lower tariffs by both countries, increased purchases by China of US farm, chemical and auto products, and new provisions to protect American intellectual property. One area where there doesn’t seem to be significant progress is on Chinese industrial policies and subsidies, which Beijing views to be central to the country’s state-led development model. Trump and Xi may meet in Florida on March 27 to sign the agreement.[5]

The US-China trade variable appears to be a net positive. If a deal is reached, it should clear major uncertainties for producers and risk-takers globally; offer some relief to Chinese risk assets (the Shanghai Composite was down nearly 25% last year)[6]; and improve US business prospects inside China.

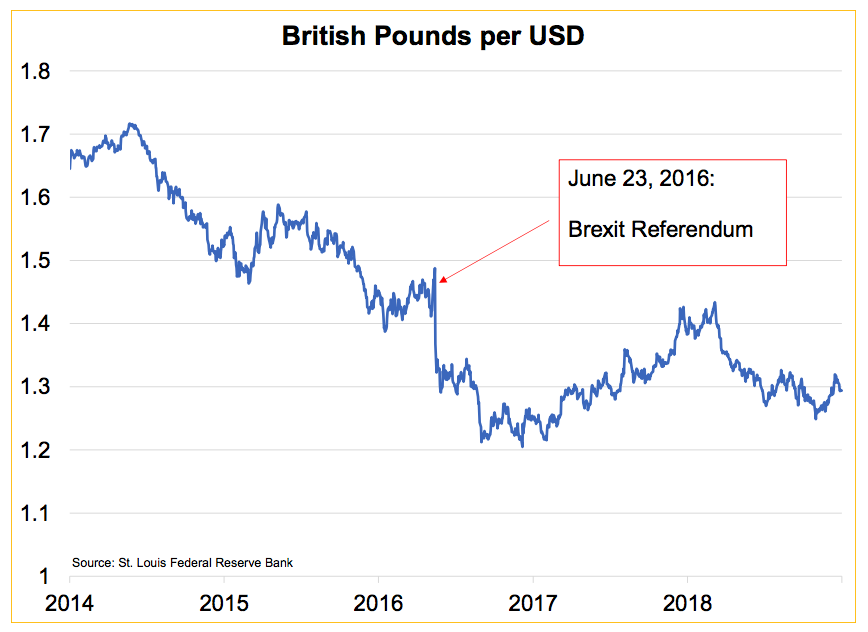

Brexit: The current plan is the UK will leave the European Union on March 29. But in our opinion, the Brexit variable is a complicated mess with no one in the world, not even Prime Minister Theresa May, certain how it’ll exactly play out.

This is an issue that doesn’t easily map onto one party in the UK. There are members in both the Conservative and Labour parties that favor Brexit, and members in both that support remaining in the EU.

For the most part, “Brexiteers” want more independence from EU rules and regulations, including the end of the free movement of labor between member countries; whereas Brexit supporters view EU membership as a guardian of the free movement of goods and people.

What makes the issue even more complicated is Northern Ireland. The “Good Friday” peace agreement in 1998 between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland was predicated to some extent on an open border between the two. And, fortunately, both UK and the EU leaders seem to agree that they want to keep it that way. In that spirit, the May government and EU leadership reached the so-called “backstop agreement”, which would keep an open border if the UK left the EU without a deal.

The backstop, however, has been rejected by the UK Parliament for a number of reasons, including concern that it would keep the UK in a customs union with the EU indefinitely (the exact opposite objective of many Brexiteers) and would create a regulatory border down the Irish Sea between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK – which is strongly opposed by many unionists whose votes are arguably propping up the May government.

Prime Minister May is still negotiating with EU counterparts to reach a deal, notably to make the Irish backstop temporary. May has promised to present Parliament with a new deal by March 12.[7] In recent weeks, it has appeared increasingly likely that if any new deal is rejected, then Parliament will have the opportunity to vote on a “no deal” Brexit (viewed by some to mean an economically messy and costly divorce) or to vote on delaying Brexit by extending the EU’s Article 50 negotiating period.[8] The majority of Parliament seems to favor a delay, and there is speculation that the Brexit deadline will be postponed by two months.

Despite the many moving parts and complicating factors, we believe the Brexit variable has marginally improved during the last month because it appears increasingly likely that a messy, no-deal Brexit will be avoided due to significant Parliamentary opposition to such an outcome, as well as its support for a delay if a deal is not reached.

That said, a delay means that the Brexit variable is simply being pushed out rather than being resolved. And, as the popular adage goes, markets hate uncertainty.

Some European business leaders like Dieter Kempf, the President of the Federation of German Industry, would rather just have a no-deal divorce to avoid the persistent uncertainty surrounding the issue. Kempf believes German firms have made sufficient plans for a no-deal scenario. “They have increased their storage capacity. They have planned a transition period for the reorganisation of logistics processes without loss of production…. My experience is that the economy can live better with bad conditions than with uncertainty.” [9] Kempf’s views, however, seem to be in the minority inside the UK Parliament.

In sum, it appears that Brexit will be delayed and markets will be forced to deal with the associated uncertainties of Brexit for many more weeks and months. We view this variable as a net negative today, although not as bad as a month ago when a no-deal Brexit scenario appeared to be a higher probability.

Slowdowns in Asia and Europe: For us, the most startling economic data out of Asia recently has been in the manufacturing sector. According to Markit, the manufacturing PMI’s in February for China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan were 49.9, 48.9, 47.2 and 46.3, respectively. This indicates that the manufacturing sectors in these major Asian economies have been contracting.

Even worse for the global economic picture, industrial production in Europe has been declining. Markit’s manufacturing PMI’s in February in Germany, the UK, France and Italy were 47.6, 52.0, 51.5 and 47.7, respectively. As the next chart illustrates, this follows significant weakness late last year, when in November and December 2018, industrial production in Germany, the UK, France and Italy each fell year-over-year.

According to Destatis, preliminary Q4 2018 GDP data revealed that the German economy grew 0.0%, narrowly avoiding a technical recession after -0.2% growth in Q3.[10] Italy’s economy, after having contracted in Q3 and Q4, is already in recession.

The U.S. economy, on the other hand, appears to be in better shape. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the economy grew 3.1% year-over-year in Q4 and 3.0% in Q3. Furthermore, ISM manufacturing PMI in the United States registered 54.2 in February; and according to jobless claims data from the Department of Labor, the American labor market appears fairly strong with claims near multi-decade lows. In sum, the United States looks to be the strongest economic region in the world, with Asia the weakest and Europe slightly better.

While slowdowns in other countries and regions threaten to mute global demand and therefore limit corporate profit growth generally, we are concerned about the risk in coming years of a severe economic slowdown leading to increased corporate defaults that in turn lead to highly distressed credit markets, including sovereign distresses.

According to data from the Institute of International Finance, Bureau of International Settlements and the IMF, total global debt in 2018 was $244 trillion; with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 382% for mature economies and 210% for emerging markets. This compares to total global debt of $74 trillion in 1997, and debt-to-GDP ratios of 266% for mature economies and 131% for emerging markets. The global economy, being so leveraged, may be more sensitive to a GDP deceleration and higher interest rates than it has been in decades.

As we see it, excess leverage doesn’t usually appear to be excessive until underlying economic fundamentals deteriorate, which in turn cause corporate profits and tax revenues to decline, so as to cause unsustainable debt burdens. In that light, we are watching, particularly closely, the economic weakness abroad and the possibility of mounting systemic risks as a consequence. To us, the slowdowns in Asia and Europe are one of the most negative macro factors today.

Trump Impeachment: According to a column in the Washington Post by Greg Sargent, “smart money” in Washington is predicting that special counsel Robert Mueller’s report, expected to be delivered soon to the Attorney General, will be a “dud”.[11] Notwithstanding, it appears that the possibility of a Trump impeachment and removal from office isn’t going away. House Judiciary Chairman Jerold Nadler said on March 3rd that he’d be requesting documents from more than 60 people “to begin investigations to present the case to the American people about obstruction of justice, corruption and abuse of power.”[12]

Although Nadler states that “impeachment is a long way down the road”, these steps could be meant to set the political foundation to pursue impeachment. While the growing belief that the Mueller Report will not directly or immediately lead to the President’s impeachment might be increasing certainty surrounding the Office of the Presidency, growing Congressional scrutiny suggests that some uncertainty is likely to linger.

Putting the Macro Pieces Together

While this is certainly not an exhaustive list of the major macro variables that exist today, it provides us with a framework to contextualize the current market environment, which looks like a “glass half full, glass half empty” kind of market.

For example, if the Fed doesn’t threaten to raise interest rates and consequently inhibit risk-taking, if a US-China trade deal is reached, a concrete resolution to Brexit emerges, Asia and Europe stabilize, and the specter of political uncertainty in the United States fades away, then there is arguably still significant upside to risk assets, even after the recent equity market rally.

And, conversely, markets could be at risk if the Fed restarts its rate-hiking campaign, a US-China trade deal is scuttled, a chaotic Brexit occurs, Asian and European economies continue to worsen, or the United States enters a Watergate-type era of political uncertainty and flux.

The macroeconomic outlook today could be reasonably described as ambiguous, which seems to be consistent with the relatively flat Treasury curve this year.

The Treasury curve in 2019 is the flattest it has been since the 2008-2009 Great Recession. And between the 2 and 5-year Treasuries, the curve is slightly inverted. But, it’s positive to see that the curve, generally, is not meaningfully inverted.

The general flatness of the curve suggests to us that the Treasury market is sensing some risks farther out on the horizon that could ultimately erupt and harm economic growth; but just not in the near-term.

And so, the glass looks half full to us today. There are percolating risks. But importantly, in our view, the dollar (the world’s reserve currency) is fairly stable, deregulation and corporate tax cuts in the United States are still supporting economic growth, and credit conditions are recently improving. We are, therefore, generally optimistic about the next 12 months as long as anti-growth policies don’t emerge in the major economies and credit markets continue to behave. Of course, we don’t expect all of the major macro variables in play today to evolve perfectly in the coming months, and some near-term volatility is likely. Indeed, the UK will need to sort through Brexit, Europe and Asia are relatively weak, and political uncertainties persist in the United States. However, counterbalancing those variables, we have a patient Fed and brightening prospects for US-China trade. We expect more equity gains in 2019, but we believe they’ll be harder to come by compared to January and February.

Paul Hoffmeister is chief economist and portfolio manager at Camelot Portfolios, managing partner of Camelot Event-Driven Advisors, and co-portfolio manager of Camelot Event-Driven Fund (tickers: EVDIX, EVDAX).

*******

Disclosures:

• Past performance may not be indicative of future results. Therefore, no current or prospective client should assume that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy (including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended by the adviser), will be profitable or equal to past performance levels.

• This material is intended to be educational in nature, and not as a recommendation of any particular strategy, approach, product or concept for any particular advisor or client. These materials are not intended as any form of substitute for individualized investment advice. The discussion is general in nature, and therefore not intended to recommend or endorse any asset class, security, or technical aspect of any security for the purpose of allowing a reader to use the approach on their own. Before participating in any investment program or making any investment, clients as well as all other readers are encouraged to consult with their own professional advisers, including investment advisers and tax advisors. Camelot Portfolios LLC can assist in determining a suitable investment approach for a given individual, which may or may not closely resemble the strategies outlined herein.

• Any charts, graphs, or visual aids presented herein are intended to demonstrate concepts more fully discussed in the text of this brochure, and which cannot be fully explained without the assistance of a professional from Camelot Portfolios LLC. Readers should not in any way interpret these visual aids as a device with which to ascertain investment decisions or an investment approach. Only your professional adviser should interpret this information.

• Some information in this presentation is gleaned from third party sources, and while believed to be reliable, is not independently verified.

[1] Source: Yahoo Finance

[2] “Powell Says Fed Is Close to Agreement on Plan to End Portfolio Runoff”, by Nick Timiraos, February 27, 2019, Wall Street Journal.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Bullard Says Patient Fed Should Mean ‘Very Good Couple of Years”, by Steve Matthews and Jeanna Smialek, February 1, 2019, Bloomberg.

[5] “China, U.S. Near Accord on Trade”, by Linling Wei and Bob Davis, March 4, 2019, Wall Street Journal.

[6] Source: Yahoo Finance

[7] “UK Likely to be Forced into Brexit Delay If PM May’s Deal Rejected”, by Kylie MacLellan, March 3, 2019, Reuters.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “German Business Terrified Short Brexit Delay Will Wreak Havoc – ‘It’s Bad for the Economy’”, by Joe Barnes, March 4, 2019, by Express.

[10] “Germany Narrowly Escapes Recession after Flat Growth in the Fourth Quarter”, by Holly Ellyatt, February 14, 2019, CNBC.

[11] “Democrats Set to Take a Big Step Toward Impeaching Trump”, by Greg Sargent, March 4, 2019, Washington Post.

[12] “House Judiciary Chairman Says He Will Launch Probe of Trump’s ‘Abuse of Power’”, by Mike DeBonis and Rachael Bade, March 3, 2019, Washington Post.